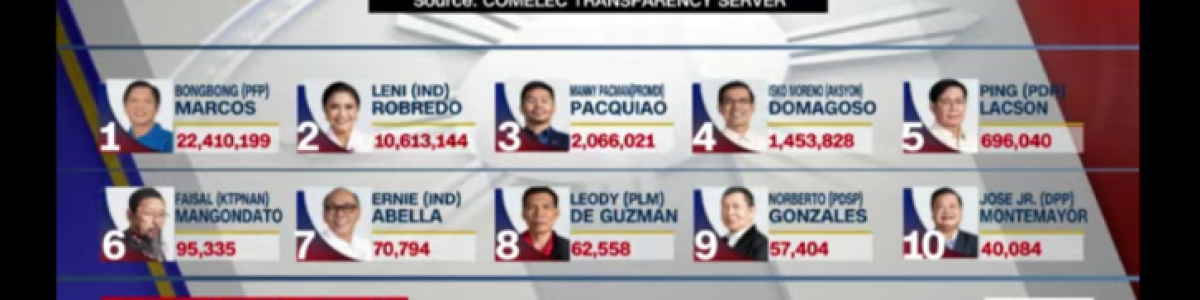

When the first words of this article are being written, the preliminary results of the Philippines’ election have already been released by COMELEC, the official election commission of the Philippines. At the first sight, the writer himself could not believe that a son of a once-toppled kleptocratic-tyrannical dictator and his cliques are making a comfortable comeback as ruler in the Philippines.

Initially, the writer tried to think that change is still possible in one of the oldest and most vibrant democracies in Asia. After all, most Philippines citizens would’ve probably learned lessons from the long periods of martial law under Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the father of the ‘victorious’ presidential candidate (BBC, 2022). Also, the years of hopelessness filled with political violence and human rights abuses during Rodrigo Duterte’s ruling had prompted some concerned Filipinos to mobilize a movement to initiate a new model of governance in the Philippines (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

But the moment the writer continued his writing, two dynasties of human rights abusers who joined their hands as Presidential-Vice Presidential candidates gained significant support from the voters.

As one of the Indonesian academics who have colleagues from the Philippines and followed the campaign trails of Philippine elections closely these months, the writer can’t help but make a parallel between the cases of the Philippines and Indonesia. While the Philippines is facing a possible kleptocratic dictatorship once again, Indonesia is also still trying to struggle to deal with the legacies of the Orde Baru regime and the tendencies of rising corruptive behaviors and political authoritarianism under Jokowi. After all these years of democratization and political reformation, what went wrong with Indonesia and the Philippines?

A Systemic Problem: What Went Wrong?

Despite the better options available for the Filipinos that were shown through the candidacy of Leni Robredo and Kiko Pangilinan as aspiring President and Vice President respectively, some Filipinos fell for the candidates who were never even attended the election debates. This brings us to the question: can we essentialize this phenomenon only to the context of developing democracies, such as the Philippines? In order to answer this question, Nicole Curato said that this phenomenon should not be exoticized only in the context of developing democracies (Curato, 2022). The rise of ‘populist’ and ‘strongman’ leaders like Victor Orban and Donald Trump is the real proof that this phenomenon is also happening in advanced democracies.

On a regional level, the symptoms of an ill democracy that resulted in the popularity of ‘strongman’ could be seen in the cases of both Indonesia and the Philippines.

Andres Ufen has even warned of a “Philippinization” of Indonesian politics since 2006. In short, Ufen tried to establish an argument that the Indonesian parties may take the shapes similar to the political machineries in the Philippines which not only lacked an ideological basis but were also prone to transactional politics and only used as a mere tool for political elites to secure their positions (Ufen, 2006). Despite the brief period of ideologization which was marked by the wave of ‘Islamic populism’ during the 2019 election, it could be seen that political parties are experiencing signs of de-ideologization (termed by Ufen as de-aliranization, similar to de-ideologization) and Indonesian political parties are increasingly influenced by strong presidentialism and party cartelization during the Jokowi era (Ufen, 2008; Slater, 2018).

In the opinion of the writer, there are several reasons which have made the quality of democracy are becoming worse, especially after the 2019 election in Indonesia and the Philippines. The first point that needs to be highlighted here is the issue of disinformation that has challenged the essence of healthy democracy in both countries. During the course of the 2014 and 2019 general elections, Indonesian voters were being presented with malicious information presented by cyber troops (also known by the name of buzzer) that were recruited by campaign teams. These cyber troops are responsible for making a deep-rooted division between kecebong (pro-Jokowi supporters – kecebong means tadpole) and kadrun/kampret (pro-Prabowo supporters – kadrun means desert lizards and kampret means bat) happening until today (The Jakarta Post, 2019). The narratives that seek to establish the importance of choosing strong leader are also apparent in the case of Prabowo, who is associating himself with the ‘successful legacies’ and ‘stability’ of New Order (Vann, 2021). The writer is therefore not surprised to see the same case is also happening in the Philippines. Bongbong Marcos and his campaign team has manipulated public opinion by framing Marcos Sr’s legacy in an exaggerated way (The New York Times, 2022). Sadly, many younger generations in Indonesia and the Philippines who lacked literacy and enough historical knowledge easily consumed this kind of propaganda without further criticism.

The second point that needs to be marked here is the strong case of political elitism in both countries, which shunned the possibility of oppositional voices being heard. While Jokowi’s victory in 2019 has seen by some as “victory of a lesser evil”, the increasing authoritarianism under Jokowi has made the quality of Indonesian democracy plunge significantly. Jokowi has always used his extensive presidential powers in order to curb many oppositional voices coming from all ideological strands, ranging from Islamist Hizbut-Tahrir to the activists of Papuan rights. Similar cases are also happening in the Philippines, where Duterte has increasingly put pressure towards journalists, environmental activists, and especially leftists.

The third point is the rampant phenomenon of money politics. This is especially a significant marker for countries which implemented crony capitalism for decades. The practice of money politics in both countries is being empowered by the clientelist networks of elite politicians who are collaborating with oligarchs. In the case of Indonesia, it is known that aspiring candidates and their success teams are spreading in-cash donations during the early hours of election day (thus known as serangan fajar or dawn attack in English). This practice could also be witnessed during the days and weeks before the Philippines’ general election this year. Atienza saw this phenomenon as solidifying the ground to sustain the negative aspects of utang na loob (debt of gratitude) (BusinessWorld, 2022).

What’s Next for the Philippines and Indonesia

To end this writing, the writer would like to emphasize that Marcos Jr-Sara Duterte’s rule in the Philippines would not be a total end for the Philippines’ democracy. Filipinos will surely face bitter times ahead, but the light will always be there. The writer himself has witnessed the campaign drive of Leni Robredo-Kiko Pangilinan mobilized by supporters who called themselves as Kakampink.

This body of supporters is not exclusively affiliating themselves with certain political parties, but they are certainly united in a strong political platform and vision to advance the agenda of democratization in the Philippines. Strengthened by Senatorial candidates who are also veteran human rights advocates such as Chel Diokno and Leila de Lima, this movement which uses rose as its symbol has certainly created a new momentum in the politics of the Philippines. The openness of its political vision has even made the candidacy of Leni-Kiko gain official support from an unlikely ally, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Seeing this, Heydarian argued that this oppositional movement would not be something that Marcos Jr can easily underestimate in the following years of his reign (Heydarian, 2022).

Facing the general election in the next two years, the writer thinks that Indonesia also needs its own “Kakampink” moment. Even if the independent presidential candidacy is still not allowed in Indonesia, a people-driven, independent presidential candidate is necessary for the betterment of Indonesian democracy.

References

BBC. (2022, May 10). Why the Marcos family is so infamous in the Philippines. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61379915

Human Rights Watch. (2017, August 17). Philippines: Duterte Threatens Human Rights Community . Retrieved from HRW: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/08/18/philippines-duterte-threatens-human-rights-community

Curato, N. (2022, May 9). @NicoleCurato. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/NicoleCurato/status/1523482322389319680

Ufen, A. (2006, December). Political Parties in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Between politik aliran and ‘Philippinisation’. GIGA Working Papers(37).

Ufen, A. (2008, March). From “aliran” to dealignment: political parties in post-Suharto Indonesia. South East Asia Research, 16(1), 5-41.

Slater, D. (2018). Party cartelization, Indonesian-style: Presidential power-sharing and the contingency of democratic opposition. Journal of East Asian Studies, 18(1), 23-46.

The Jakarta Post. (2019, March 30). Of tadpoles and small bats: How name calling deepens Indonesia’s great political divide This article was published in thejakartapost.com with the title “Of tadpoles and small bats: How name calling deepens Indonesia’s great political divide. Retrieved from The Jakarta Post: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/03/30/what-is-cebong-kampret-indonesian-politics-jokowi-prabowo-election.html

Vann, M. (2021, September 29). Indonesia Still Hasn’t Escaped Suharto’s Genocidal Legacy . Retrieved from Jacobin: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/09/indonesia-sukarno-suharto-communists-genocide-dictatorship-corruption

The New York Times. (2022, May 6). In the Philippines, a Flourishing Ecosystem for Political Lies . Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/06/business/philippines-election-disinformation.html

BusinessWorld. (2022, February 14). Filipinos start taking the money as campaign period begins amid a pandemic . Retrieved from BusinessWorld: https://www.bworldonline.com/top-stories/2022/02/14/429707/filipinos-start-taking-the-money-as-campaign-period-begins-amid-a-pandemic/

Heydarian, R. (2022, May 10). Emphatic Marcos victory no cause for panic . Retrieved from Nikkei Asia: https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Emphatic-Marcos-victory-no-cause-for-panic